It is

nearly impossible to sum-up over-riding themes in a year of cinema, but its

almost impossible to resist the temptation to do so. American cinema is nearly

always the easiest to do so, due to the availability of such films, so I have

attempted to place some re-occurring themes and matched them with corresponding films.

I have also listed some key films from around the world that have either made

an impact on cinema this year, or on me. This has meant some films mentioned I

have not seen, but deserve to be mentioned due to their impact on others.

American

cinema seems to have been mostly concerned with two, twinned themes. Isolation

and Technology, and Inequality and Celebrity/Excess. These themes are

unavoidable in modern day America, and therefore is of no surprise they have

often cropped up. These themes have also been occasional supported by other key

films from across the globe, but have been placed alongside American

counterparts to support the idea.

Isolation

Upstream Color (Carruth)

Long anticipated second feature by Carruth. Represents isolation and connection

through artificial means, all while only ever telling fragments of story at a

time. Key American independent film.

Gravity (Cuaron)

Most

clear-cut film about isolation, Gravity

contrasts the vastness of space with the emotions of one human. Perfect blend

of Hollywood scale and creativity.

Her

(Jonze)

Leviathan (Castaing-Taylor and Paravel)

Technology

The Worlds End (Wright)

Last

of the trilogy, The World’s End examines

how technology and commercialisation is removing the heart and soul of the

United Kingdom.

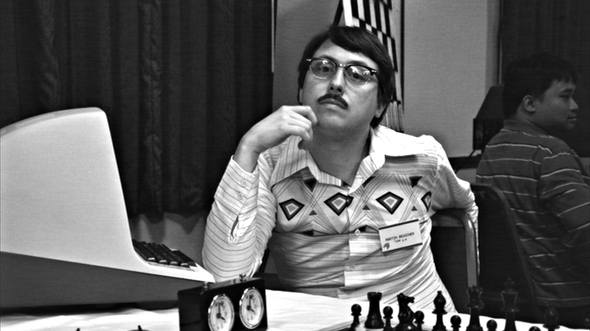

Computer Chess (Bujalski)

Incredibly creative, Bujalski’s latest feature looks at the fear of technology from the

80s, and how what seemed strange then, is beyond normal now. That’s all until

the ending…

Inequality

Elysium (Blompkamp)

Not as

great as District 9, but still able

to present more challenging ideas than most Hollywood blockbusters would ever

attempt to do. By taking on an extremely relevant subject matter in America

right now, Blompkamp was always likely to split audiences. His vision however

of the future is distinctive and beautiful. Both on Earth, and on Elysium.

The Purge (DeMonaco

Altogether ignored by critics, The Purge is an examination

on white-middle class America, and how it demonises the poor. Unafraid to

explore racism and prejudice. If Haneke made an American genre film.

12

Years a Slave (McQueen)

Captain

Phillips (Greenway)

Fruitvale

Station (Coogan)

The

Immigrant (Gray)

Celebrity and Excess

The Great Beauty (Sorrantino)

Wondering

and beautiful, The Great Beauty shows

post-Bunga Bunga Italy. Shows the hollowness of extreme wealth.

The Bling Ring (Coppola)

Celebrity

obsession. Coppola takes an interesting story and allows her actors the freedom

to really embrace all of their silliness and contradictions. The American dream

has become wanting more for nothing.

Pain and Gain (Bay)

Similar

themes in Pain and Gain to The Bling Ring. Dismissed due

to Bay being the director. Is funny, over the top, and slightly over-long,

however does a fantastic job at showing how the American dream has become

corrupted.

The

Wolf of Wall Street (Scorsese)

The Lone Ranger (Verbinski)

A film

not so much about excessiveness, but is the embodiment of the idea itself.

Unfair criticism for the film damaged from start, but has already seen some

retrospective consideration.

Key Asian

Wadjda

(Al-Mansour)

Sold

on the fact that it is the first Saudi film by a Woman, Wadjda has a lot more going

for it than just that. Funny, and heartfelt.

Shady

(Watanabe)

Biggest

unknown, seen at the Raindance Film Festival. Completely sucks you in. The

subtle tonal shifts throughout are incredibly done.

Stray

Dogs (Ming-liang)

Like

Father, Like Son (Koreeda)

A

Touch of Sin (Zhengke)

The

Act of Killing (Oppenheimer)

Topping

a number of End of Year lists, The Act of

Killing is perhaps the must-see documentary this year.

The Grandmaster (Kar-wai)

Blind

Detective (To)

North/South America

La Reconstruccion (Taratuto)

An Argentinian look at isolation, set in the deep

cold South. The performance of Diego Peretti is a stand-out.

From

Tuesday to Tuesday (Trivino)

Short Term 12 (Cretton)

Tom at the Farm (Dolan)

Prinsoners (Villeneueve)

Africa

Grigris

(Haroun)

Although

not as well received as previous effort, A

Screaming Man, it is still of note due to the fact it is the only African

film this year to break into the a main competition at this years festivals.

Mother

of George (Dosunmu)

Europe

Blue is the Warmest Colour (Kechiche)

Beneath

the controversy about the director/actress relationship, and the (shock horror)

lesbian roles, Blue is the Warmest Colour

is a perfectly pitched love/break-up story.

The

Past (Farhadi)

Bastards

(Denis)

Child’s

Pose (Netzer)

Under

the Skin (Glazer)

The

Selfish Giant (Bernard)

The

Double (Ayoade)

Ida (Pawlikowski)

Museum Hours (Cohen)